The OG Mary Sue Rant

First, the Background

One of the pleasures of blithely diving in as a first time novelist is learning the lingo and hangups of writers themselves. That happened to me a few weeks back while reading a Reddit thread where people were saying this or that character is “such a Mary Sue” and I had no idea what the hell they meant.

So I googled. And here’s what Wikipedia had to say:

The Mary Sue is a character archetype in fiction, usually a young woman, who is often portrayed as inexplicably competent across all domains, gifted with unique talents or powers, liked or respected by most other characters, unrealistically free of weaknesses, extremely attractive, innately virtuous, and generally lacking meaningful character flaws. Usually female and almost always the main character, a Mary Sue is often an author’s idealized self-insertion, and may serve as a form of wish fulfillment. Mary Sue stories are often written by adolescent authors.

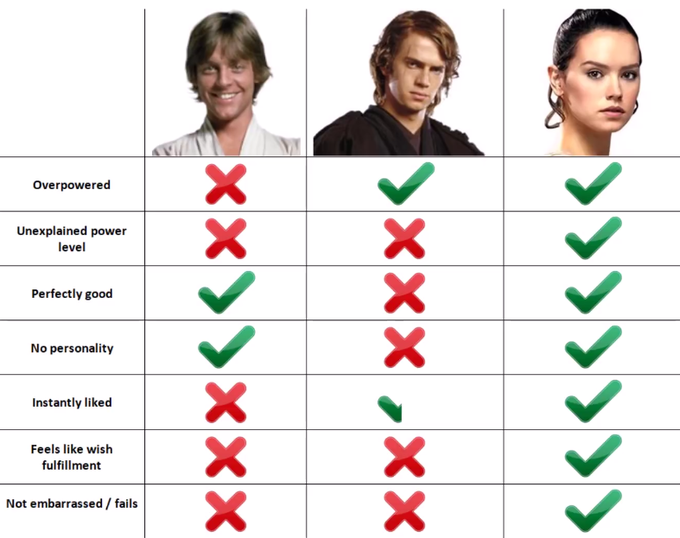

And here’s a popular meme that popped up:

I don’t have strong opinions on whether Rey is a Mary Sue or not, but I’ll agree that her character felt kinda flat.

Then it turns out we’re all misogynists for even using the term.

How dare we.

Except…

I had the distinct impression in the romantasy sub-Reddit thread that most of the commenters using the term were women.

And, the two writers who originally defined the trope were women too (Paula Smith and Sharon Ferraro in the Star Trek fanzine Menagerie, in 1973).

Here’s the whole text of A Trekkie’s Tale, the parody story that started it all:

“Gee, golly, gosh, gloriosky,” thought Mary Sue as she stepped on the bridge of the Enterprise. “Here I am, the youngest lieutenant in the fleet - only fifteen and a half years old.” Captain Kirk came up to her. “Oh, Lieutenant, I love you madly. Will you come to bed with me?” “Captain! I am not that kind of girl!” “You’re right, and I respect you for it. Here, take over the ship for a minute while I go get some coffee for us.” Mr. Spock came onto the bridge. “What are you doing in the command seat, Lieutenant?” “The Captain told me to.” “Flawlessly logical. I admire your mind.”

Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy and Mr. Scott beamed down with Lt. Mary Sue to Rigel XXXVII. They were attacked by green androids and thrown into prison. In a moment of weakness Lt. Mary Sue revealed to Mr. Spock that she too was half Vulcan. Recovering quickly, she sprung the lock with her hairpin and they all got away back to the ship.

But back on board, Dr. McCoy and Lt. Mary Sue found out that the men who had beamed down were seriously stricken by the jumping cold robbies, Mary Sue less so. While the four officers languished in Sick Bay, Lt. Mary Sue ran the ship, and ran it so well she received the Nobel Peace Prize, the Vulcan Order of Gallantry and the Tralfamadorian Order of Good Guyhood.

However the disease finally got to her and she fell fatally ill. In the Sick Bay as she breathed her last, she was surrounded by Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy, and Mr. Scott, all weeping unashamedly at the loss of her beautiful youth and youthful beauty, intelligence, capability and all around niceness. Even to this day her birthday is a national holiday of the Enterprise.

So I filed that away in the back of my mind and went back to writing my story, now slightly more paranoid about accidentally making my character Cora into a Mary Sue, but otherwise not thinking much about it.

The Victorian Connection

Until a few days ago…

…When I realized there was something really familiar about the Mary Sue gripe. Something that I had even referenced in my novel. In 1856, George Eliot (a woman, in case you were thrown by the name), published an essay titled Silly Novels by Lady Novelists. And I’ll be damned if she didn’t rant about the Mary Sue archetype, in different words, over a hundred years before Paula Smith did. Check this out:

The heroine is usually an heiress, probably a peeress in her own right, with perhaps a vicious baronet, an amiable duke, and an irresistible younger son of a marquis as lovers in the foreground, a clergyman and a poet sighing for her in the middle distance, and a crowd of undefined adorers dimly indicated beyond. Her eyes and her wit are both dazzling; her nose and her morals are alike free from any tendency to irregularity; she has a superb contralto and a superb intellect; she is perfectly well dressed and perfectly religious; she dances like a sylph, and reads the Bible in the original tongues. Or it may be that the heroine is not an heiress—that rank and wealth are the only things in which she is deficient; but she infallibly gets into high society, she has the triumph of refusing many matches and securing the best, and she wears some family jewels or other as a sort of crown of righteousness at the end. Rakish men either bite their lips in impotent confusion at her repartees, or are touched to penitence by her reproofs, which, on appropriate occasions, rise to a lofty strain of rhetoric; indeed, there is a general propensity in her to make speeches, and to rhapsodize at some length when she retires to her bedroom. In her recorded conversations she is amazingly eloquent, and in her unrecorded conversations amazingly witty. She is understood to have a depth of insight that looks through and through the shallow theories of philosophers, and her superior instincts are a sort of dial by which men have only to set their clocks and watches, and all will go well. The men play a very subordinate part by her side. You are consoled now and then by a hint that they have affairs, which keeps you in mind that the working-day business of the world is somehow being carried on, but ostensibly the final cause of their existence is that they may accompany the heroine on her “starring” expedition through life. They see her at a ball, and they are dazzled; at a flower-show, and they are fascinated; on a riding excursion, and they are witched by her noble horsemanship; at church, and they are awed by the sweet solemnity of her demeanor. She is the ideal woman in feelings, faculties, and flounces.

The reference in my novel is when Julian shows Cora their new library, and the corner that has all of Cora’s favorite books in it, including some “silly novels by lady novelists” that Cora liked. Ironically, my name-dropping of George Eliot there pushes Cora further into Mary Sue / silly-novel-heroine territory. George Eliot again:

she makes up for the deficiency by a quite playful familiarity with the Latin classics—with the “dear old Virgil,” “the graceful Horace, the humane Cicero, and the pleasant Livy;”

So, casual references to literary figures are themselves part of the problem.

I make no apologies. :)

The Misogyny Thing

The important thing to remember here is that multiple things can be true at the same time.

Are there bitter gatekeeping incels (another sexist term) deploying the term “Mary Sue” in misogynistic ways?

Absolutely.

Is there a common trap where inexperienced writers indulge their own wish fulfillment by putting too-perfect characters into the story?

Also yes.

Is it more common for that to happen with female characters than male characters?

No idea. Do a study. Count things.

Are we more likely to complain when it happens with female characters than male characters?

Probably. And yeah that’s sexist. But some of the examples I’ve seen where we give male characters a pass for being “Gary Stu” are like, James Bond. To me it’s a different gripe when you complain about an overpowered-but-seasoned grown up character than when you complain about an inexplicably-competent teenager.

So What Do We Do About It?

Just write your stories. Make your characters awesome. Make your characters believable. Or not.