Why Do We Love "Modiste" So Much?

I have a theory. Sometimes we fall in love with certain inaccurate ideas of how life used to be in a certain time and place. And then if we see a more accurate depiction, it feels wrong. I’ll give three examples.

Example 1: Modiste

Like lots of people, I’ve been enjoying Bridgerton. And from Bridgerton I learned the word “modiste”. And I was close to using it in my story, but decided to do a little googling first to make sure I used it correctly. And it seemed like most of the usages I found there were Bridgerton references.

I decided to use a different word, and then a reader asked “wouldn’t they call it a ‘modiste’?”

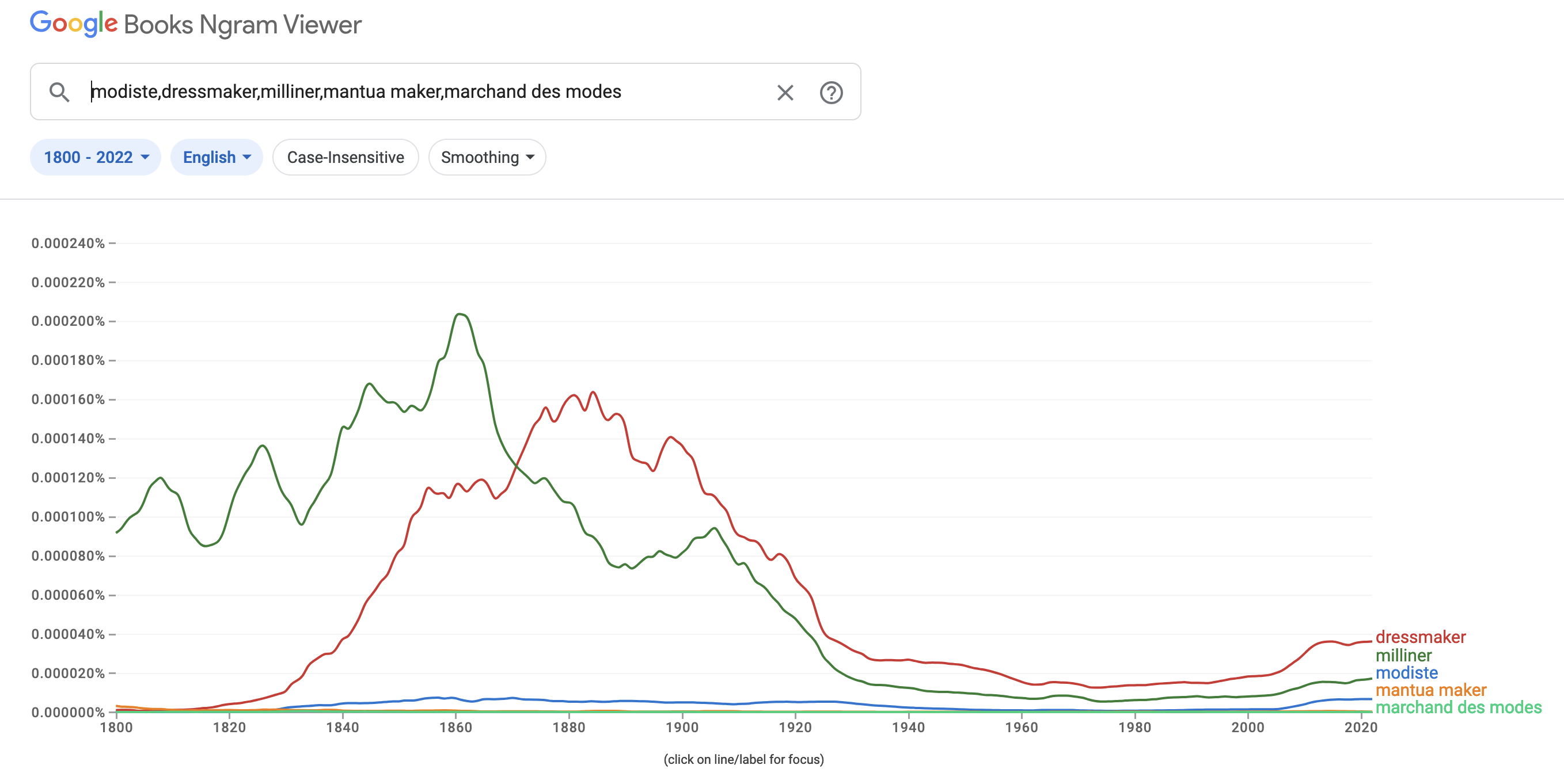

So I did what I should have done in the first place, and consulted the Google Ngram Viewer. Being able to search for word frequencies across several centuries’ worth of books is astonishingly valuable for helping me to know what words people actually used in previous eras, especially in the English-speaking world. I’m probably in there running different searches a dozen times a day when I’m writing new chapters.

Here are the results of comparing several different terms for people who made women’s dresses:

I take a few things from those results:

- People actually did use “modiste”!

- But it wasn’t nearly as common as dressmaker and milliner.

- “Modiste” was relatively more popular in the mid Victorian era than it was in Regency times.

Credit to Beatrice Knight’s post on A List of Dressmakers in Regency London for tipping me off to the other terms. I wouldn’t have thought of searching for “milliner” if she hadn’t suggested it. But apparently it could mean dressmaker as well as hat maker until the later Victorian period.

Interestingly, Knight’s own “Regency Modistes’ Compendium” also puts the word “modiste” in the title. I don’t know when she decided on that name, but with a publication date in Dec. 2023 it could still be a product of the “Bridgerton effect”.

What’s most interesting to me is why we fall in love with words like that. If I remember back to when I first heard it, I remember feeling “Oh, that’s a new word. I didn’t know they said that back then. It has a romantic flair to it. I like it.” I suspect that Bridgerton chose it because their dressmaker character is attempting to accentuate her French-ness. (The more you learn about that character, the more sense that makes.)

Example 2: Those Collars in Emma

The Emma movie that came out in 1996 was great. Here’s Jeremy Northam playing Mr. Knightley in it.

His collar is big, but I don’t remember being distracted by it at the time.

And here’s Johnny Flynn playing the same character in the 2020 version.

Someone please rescue this man. He is being eaten by his shirt.

The thing is, I have no idea which depiction is more true to the period. I do know that when I watched the 2020 version, I was completely taken out of the wedding scene because I could not get over the size of all the men’s collars.

Example 3: Sex Talk

Sex talk is hard to get right even without adding concerns about historical accuracy. It is impossible to please everyone, and the people who are displeased are likely to be very displeased. In a contemporary steamy romance you have three options (children, cover your ears here):

- Dirty slang. Her tits heaved as she guided his cock into her tight pussy. Now you just lost the readers who dislike bad words.

- Creative euphemisms. Her bosom heaved as she guided his throbbing member into her tight depths. Now we’re all rolling our eyes after seeing the word “member” for the thousandth time.

- Medically technical. Her breasts heaved as she guided his penis between her labia and into her vagina. Now the readers feel like their feet are up in stirrups at an OB/GYN visit.

Of course, not all of those are alike. Sometimes we have decent middle-of-the-road words like “nipples” and “breasts”.

If you’re writing historical fiction you have a fourth option:

- Historic dirty slang. Her bubbies heaved as she guided his prick into her cunt. Now you have really lost folks because “cunt” is an even more polarizing word these days. It’s either very dirty and turning off even more people than “pussy”, or used with ironic distance. And the readers who don’t get hung up there are scratching their heads thinking “bubbies? Really?” There are a lot of even more obscure options here, like “gamahuche” for oral sex or “St. George” for the cowgirl position.

What’s extra hard about trying to pull off that last option is that we don’t actually have a great idea what words people used in private. We do have some written sex scenes (see, for example, some old issues of The Pearl) but I get the feeling they were written more to be outrageously titillating than to represent peoples’ typical experience. So the Google Ngram Viewer is not as useful here.

But What Do I Do?!

The wild thing is that we have fashions and trends in how we depict the fashions and trends of earlier times. For a writer, that creates an interesting dilemma. Do I use the current fashions in a way that will be less distracting to the reader (and risk my book being too much a product of my time), or do I stick closer to the way people actually used words back then, and risk alienating the reader? Sometimes it’s actually the more modern word that will be distracting, as the readers of your period romance are left thinking “I don’t think people talked like this back then.”

As much as I would like a simple rule here, I just don’t think it’s possible. Every occurrence is a balancing act. Sometimes I want to emphasize that the past was different, and will reach for historical accuracy.

Sometimes I want to cultivate a different emotion, and will reach for a less-distracting modern alternative.

And in some cases I will probably take the get-off-my-lawn approach of raging against the modern fashions and reminiscing about “In my day…”

I think that’s what I’m gonna do with “modiste”.